What is AML?

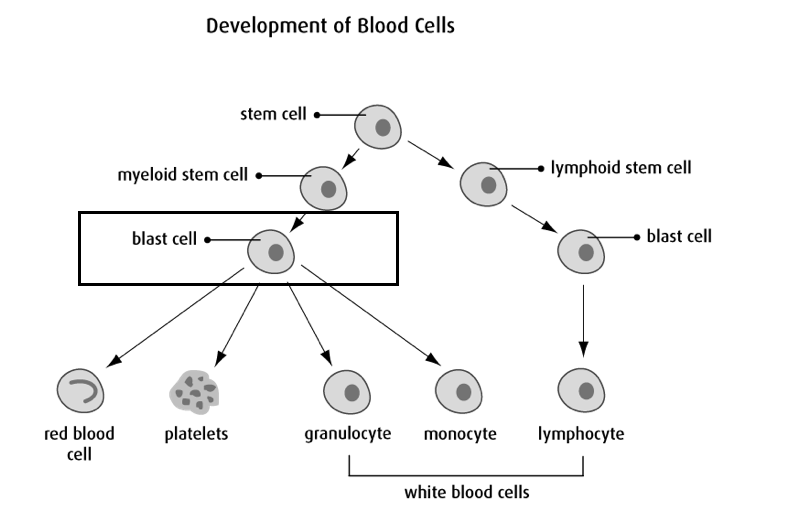

Leukemia is a cancer of the blood and bone marrow. Bone marrow is the spongy, soft center of bones where stem cells are formed. Some stem cells in the bone marrow mature to form different types of blood cells:

- Red Blood Cells – These cells carry oxygen from your lungs to all parts of your body.

- Platelets – These cells help the body form clots to prevent and stop bleeding.

- White Blood Cells – These cells help the body fight germs and prevent infection.

Cancer is the uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells in your body that can cause damage to other organs and tissues. In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), it is the uncontrolled growth of immature, abnormal blood cells sometimes called “blast cells” (see diagram above). It is normal for a small number of blast cells to be present in the bone marrow, but in case of AML a large number of abnormal blasts cells start to overtake the bone marrow.

Diagnosis

Patients suspected of having AML require a bone marrow biopsy for confirmation of diagnosis. A bone marrow biopsy is a procedure in which a small sample of bone and bone marrow are collected from your bone. Please see Diagnostic Tests and Procedures for more information.

Treatments

Note: We are attempting to provide patients with information on the most common treatment utilized; however, it is ultimately up to the Transplant Physician to determine the safest recommended course of action for each individual patient.

Chemotherapy medications are anti-cancer drugs that can be injected into a vein or muscle or taken by mouth, in an attempt to control or kill cancer cells. These drugs enter the bloodstream and spread throughout the body. The chemotherapies that are prescribed have been very carefully planned as part of a protocol just for you. Before your treatment begins, your physician will review the risks and benefits with, then ask you to sign an informed consent.

Chemotherapy is an important part of your treatment and will consist of one or more different types of medications depending on the type of disease you have. The chemotherapy is given on a special schedule that is thought to be best for killing your cancer cells while minimizing the harm your body. Your doctor will discuss with you what days you will receive chemotherapy, the type of chemotherapy and how you should expect to feel.

Younger patients with AML are usually treated with induction chemotherapy, usually requiring 2 types of intravenous (IV) chemotherapy: one given for 3 days and one given for 7 days. You will hear this commonly referred to as “7+3” chemotherapy.

The goal of “induction” chemotherapy is to “induce” a complete remission and another bone marrow biopsy will be done around 4 weeks after starting treatment to determine if the patient is in complete remission. Complete remission is achieved when there is less than 5% blasts in the bone marrow and normal recovery of blood counts. After complete remission is achieved, further chemotherapy treatment, called consolidation chemotherapy, is given to attempt to cure the leukemia. Consolidation chemotherapy is usually given in 2-3 cycles and can be administered in the inpatient or outpatient settings. If a patient does not achieve remission, or the leukemic cells return, more chemotherapy treatment will be required.

If your physician has informed you that you will be receiving 7+3 induction chemotherapy, you can download and reference the module below for more thorough information regarding this chemotherapy treatment.

All-Trans Retinoic Acid (ATRA)

ATRA, a derivative of Vitamin A, is a highly effective treatment for the M3 variant of AML, also known as acute promyelocytic leukemia or APL. ATRA is NOT a useful drug for other forms of AML.

Arsenic Trioxide

Arsenic compounds have shown to be effective in acute promyelocytic leukemia. It is commonly given in combination with ATRA as induction chemotherapy for APL.

In some cases, a stem cell transplant may also be considered after remission to try and cure the leukemia. Generally, stem cell transplant offers a better chance of preventing the leukemia from returning than chemotherapy alone but it is also a more risky treatment that can lead to more complications and side-effects. The decision of whether or not to undergo stem cell transplant can be complicated and AML patients and physicians will discuss the pros and cons of this approach.

Stem cells are “baby cells” that can grow into many different types of cells. They are able to recognize what type of cells require replacement in the body, and will mature into this particular cell. A stem cell transplant may be used for some patients with AML to try to replace the patient’s cancer cells with a donor’s healthy stem cells.

If an individual is a candidate for a transplant, patients with AML receive an allogeneic stem cell transplant. Allogeneic refers to the type of transplant where stem cells are collected from a donor, either a relative or a volunteer donor. The donor stem cells can be collected from the donor’s bone marrow or the blood; however, it is more common practice to collect stem cells from the donor’s blood as it is a less invasive procedure.

The transplant itself is also a non-invasive procedure. The stem cells will be infused into the patient through an IV line that goes into their bloodstream. A nurse will be administering the stem cell transplant and they will remain with the patient the whole time. The infusion of cells generally takes only 30 minutes to 1 hour.

Note: A stem cell transplant may not be an appropriate treatment option for some patients, and therefore not all patients with AML will receive one.

If your Transplant Physician has informed you that you are going to receive a stem cell transplant, you can download and reference the module below to obtain more thorough information regarding the allogeneic transplant process.

Side Effects and Complications

Most people find it helpful to have information about side effects so they know what to expect and how to manage them. Although the side effects of treatment can be unpleasant, it is important to know that they are usually temporary. Many of these side effects and complications can be treated with medications and careful monitoring.

Remember that all patients are unique. No two persons will have the same experience with side effects. The degree and intensity of each possible side effect also vary greatly from person to person.

Your BMT healthcare team will work closely with you to minimise any discomfort that you may have as a result of your treatment.

What Are the Common Side Effects?

During your therapy, the nurses and doctors will refer to your blood counts. These are the cells in your blood stream that are made by your bone marrow, the factory of all our blood cells. Chemotherapy affects the bone marrow’s ability to make these cells.

The blood counts to which the nurses and doctors will refer are the hemoglobin, platelets, and neutrophils. Let’s discuss each one of them:

1. Hemoglobin:

Anemia is a condition in which you don’t have enough healthy red blood cells to carry adequate oxygen to the body’s tissues. The blood count that measures our anemia is hemoglobin.

Some treatments can reduce your red blood cells and cause anemia. You may feel very tired, weak, dizzy or short of breath. You may notice that your skin, gums, and nails are pale. The symptoms will improve as your body produces more red blood cells. We monitor your hemoglobin to tell us how anemic you are, and to determine if you will need a blood transfusion.

What can help with symptoms of anemia:

- Tell your health care team if you are feeling dizzy or weak. Depending on your hemoglobin value, you may receive a blood transfusion.

- Move slowly to avoid getting dizzy. When you get out of bed, sit on the side of the bed for a while before you stand up. Once you stand up, ensure you feel stable on your feet before you start walking.

- If you’re feeling weak or dizzy, call a nurse (or family member when at home) to help you. This is not an imposition; it is much safer for you to accept help than for you to fall and injure yourself.

- Limit your activity to what is tolerable to you.

2. Platelets:

Platelets are cells that help the blood to clot. Some chemotherapy drugs can cause your bone marrow to make fewer platelets. If you have a very low platelet count, you may get symptoms such as:

- Bruises on the skin without an apparent injury

- Bleeding from the gums or nose

- Blood blisters in the mouth

- Pinhead-sized red spots in the skin, especially on the lower legs and feet. These are called petechiae (“puh-tee-kee-ah”).

- Blood in the urine or stool

You may need a platelet transfusion if your platelet count drops too low, or if you are bleeding from low platelets, or before certain invasive procedures.

What can help when you have low platelets:

- Talk to your nurse or doctor about any bleeding or bruising issues. Depending on your blood count results, we may give you a platelet transfusion.

- Certain medications can affect the way platelets function. Ask your doctor before you take aspirin, ibuprofen, or other over the counter or prescribed medications.

- Blow your nose gently to prevent a nosebleed. Do not pick your nose.

- Use a very soft toothbrush or cotton swabs to clean your teeth.

Use an electric shaver instead of a razor. Electric shavers are available for use on the inpatient unit; ask your nurse. - If you are female and are having heavy bleeding from your menstrual period, talk to your nurse or doctor.

- Be extra careful when you use a knife, scissors or any sharp tool.

Call us immediately if you have any of the following:

- Vomit that looks like black coffee grounds

- Black, tarry bowel movements

- Bright red blood in your urine or stool

- New onset, severe headache

3. Neutrophils:

Neutrophils are one of the types of white blood cells. These cells are important in protecting you from infection. Chemotherapy will temporarily affect your bone marrow’s ability to make neutrophils. A fever can be a sign of infection. If you have a fever when your neutrophils are low, we may need to act quickly to give you antibiotics to stop a potential infection from causing serious harm.

What you can do to help when you have low neutrophils:

- Take your preventative medications (antibiotics, antifungals and antivirals) as instructed. These medications help protect you from infections while your white blood cells are low.

- Proper and frequent handwashing is the best way to prevent infections. Carry a bottle of hand sanitizer when you are out of your home.

- Check your temperature twice a day: in the morning and early evening. Check it more often if you’re feeling unwell.

- Do not take Tylenol® (acetaminophen) unless we instruct you to.

- Call us immediately if you have any signs of an infection including:

- A fever. This is a temperature of 38°C (100°F) or higher.

- Feeling chilled, tremulous, lightheaded, dizzy or faint

- Burning or pain when you urinate.

- Areas of the skin that are red and hot, especially around any intravenous or “line”site

- Cough, shortness of breath, or chest pain

- Family and friends should NOT visit you if they have any signs of illness (i.e. new cough, fever, diarrhea, vomiting, sore throat, runny nose, etc.).

- Shower daily or every other day. Keep your body clean.

- Clean your anal area gently but thoroughly after a bowel movement. Wipe from the front (genitals) to the back (rectum) to avoid urinary tract infections.

- Avoid touching your face and mouth with your hands.

- Avoid crowded areas such as malls, markets, buses, and movie theatres.

- Do not go swimming or use hot tubs if you have an indwelling IV line or a low white cell count.

How and When to Take Your Temperature:

- Take your temperature with a digital thermometer in Celsius twice a day: when you get up in the morning and in the early evening (around 6pm).

- Take your temperature more often if you don’t feel well.

- Don’t take your temperature after eating or drinking. Wait 5 minutes.

- Clean your thermometer with warm water and dish soap. Allow to air dry.

- Call us immediately if you have a fever of 38°C (100°F) or higher. We will give you instructions to follow.

Undergoing cancer treatment can affect every part of your life, including your body, feelings, relationships, self-image and sexuality. Some patients say that the emotional impact of treatment can be harder to manage than the physical changes.

Anxiety is feeling afraid, overwhelmed or very worried. Depression may make you feel hopeless, isolated or fearful. If any of these feelings have overwhelmed you, tell your healthcare team. They can refer you to a support group or psychiatrist, or give you medicine that can help.

Some of your required medications may make anxiety or depression worse. It is important to tell us how you feel so that we may adjust these medications if necessary.

What you can do to help:

- Let your health care team know you are feeling anxious. We can listen and help reassure you. Ask us questions so you will know what to expect.

- Write down your thoughts or share your feelings with people you trust.

- Try to engage in at least light physical activity. A 10-15 minute walk each day outside may boost your mood and energy.

- Try to participate in an activity you enjoy. Reading, meditation, listening to music, watching a favourite TV show or movie, painting, sketching or knitting, can all take your mind off your

- Look for relaxation and meditation apps for your portable device (i.e. Calm® and Headspace® apps can be trialed for free before purchasing).

- Try relaxation techniques such as deep breathing, meditation, reiki or yoga.

- Set realistic, small goals. When you feel overwhelmed, try limiting your outlook to one day or even one hour at a time. This helps you focus on the here and now and see your progress one step at a time.

While you’re receiving treatment, your body needs more energy than usual. Eating helps you heal. Getting enough calories, proteins, vitamins and minerals will help prevent muscle loss.

You may not feel like eating because of nausea, a sore or dry mouth, fatigue, taste changes, stress, or just low appetite.

What you can do to help:

- Ask your nurse for a referral to one of our dietitians. They can offer helpful suggestions specific to your situation.

- Eat whatever you can manage, even if this means eating the same foods for a while. Your taste sensations will eventually improve.

- Instead of big meals, eat smaller meals and snacks more often.

- Relax and take your time while eating. Eat when your energy is highest.

- Eat what works for you. Eat breakfast foods at suppertime if you feel like it.

- Try to add calories and protein to meals: peanut butter, higher fat milk, cream, eggs, cheese, yogurt, tofu, gravies, ice cream, nuts, beans.

- Higher nutrient fluids: fuller fat milk, smoothies, meal replacement drinks, cream soups, and hot chocolate. (Caution: dairy products can cause diarrhea, in some circumstances).

- Light exercise and a walk before meals can help boost your appetite.

- Be patient – your appetite will come back.

Constipation means you’re not having bowel movements as often as you used to. Your stool becomes hard and dry, and having a bowel movement can be difficult or painful.

Changes in your normal bowel movements may be caused by drug treatments for cancer or other drugs you’re taking to manage the side effects of therapy. Constipation can also happen because you’ve changed your eating habits, you’re drinking less liquid or you’re less active.

What you can do to help:

- Talk to your nurse, dietitian and doctor. They can help suggest stool softeners, laxatives and other diet options that can help with constipation symptoms.

- Add more fibre to your diet, a little at a time. Examples of foods with high fibre are whole grain breads and cereals, brown rice, vegetables, fruit (including dried fruit), legumes, beans, seeds and nuts.

- Drink plenty of liquids throughout the day. Try water, fruit or vegetable juices, tea or hot cocoa.

- Eat natural laxatives such as prunes, prune juice, coffee, and papaya.

- Be more physically active. Just taking a walk can help.

- Do not strain to have a bowel movement. This can cause issues with bleeding, infection and hemorrhoids.

- Do not use any rectal suppositories or enemas while receiving treatment. They can cause bleeding and increase the risk of infection.

Diarrhea means you have soft, loose or watery stools. You may also have cramps and bloating or feel an urgent need to have a bowel movement. It is important to tell your healthcare team if you have diarrhea so we can determine the cause and how we can help you best manage it.

What you can do to help:

- Tell your nurse or doctor if you have diarrhea. Depending on how frequent it is, a sample may be taken to test for infection.

- Use soft toilet paper. Clean your bum with mild soap and water after each episode of diarrhea. Rinse well and pat dry with soft toilet paper.

- Tell your nurse or doctor if you have any pain or bleeding in your rectal area.

- Drink plenty of fluids. Try water, broth, diluted fruit juices, or caffeine free sport drinks.

- Eat high potassium foods such as bananas, apricots and peach nectars, meats and potatoes.

- Limit intake of irritants such as coffee, chocolate and prune juice.

- Ask your doctor before taking any over-the-counter medications for diarrhea.

- Ask your nurse about the use of protective barrier creams you can use to reduce the amount of skin irritation from frequent wiping.

Nausea is when you are feeling sick to your stomach and feel like you have to throw up (vomit). Many of our chemotherapy drugs, other medications, and some of the toxicities (like mucositis) from chemotherapy can cause nausea and vomiting.

What you can do to help:

- Talk to your nurse, doctor and dietitian for strategies to help reduce nausea and vomiting.

- Take prescribed anti-nausea pills as instructed and take more “as needed”.

- Instead of big meals, eat smaller meals and snacks more often.

- Avoid foods that are very sweet, greasy, fried or spicy or that have a strong smell.

- After eating, avoid lying down for at least half an hour.

- Relax and take your time while eating.

- Sip water and other liquids (ginger ale, sports drinks, broth) throughout the day.

- If you’re feeling nauseated, take deep slow breaths through your mouth or place a cool cloth over your eyes and forehead.

- Smelling (not eating) aromatherapy oils can be helpful with nausea.

- Cannabis has anti-nausea effects although its use on hospital property is restricted. For more information, talk to your healthcare team.

Foods and fluids that may be easier to eat:

- Broth, water, peppermint tea, ginger tea

- Popsicles, watered-down juices, Gatorade®, “flat” pops (i.e. ginger ale)

- Jell-O®, sherbet

- Soda crackers, Melba toast, pretzels, dry cereals, dry toast, plain cookies

- Boiled potatoes, noodles, rice, congee

- Light soup – chicken and rice, vegetable

- Boiled or baked lean meat, poultry and fish

- Skim or 1% milk, low fat yogurt, cheese

- Applesauce and fresh, frozen or canned fruit and vegetables

Avoid foods that can make nausea worse:

- Fried meats, fried eggs, sausage, bacon

- Broccoli, brussel sprouts, onion, garlic

- Doughnuts, pastries, coffee, other rich sauces and foods

When Should I take “As Needed” Anti-Nausea Medications?

Your doctor will prescribe you anti-nausea medications to take “as needed.” They can be given in pill or capsule form or, while you’re in hospital, intravenously (IV).

Anti-nausea medicines work best when you take them before or as you’re starting to feel sick. They may not work as well if you take them just as you are about to throw up (vomit). If you’re feeling nauseated and one medication doesn’t work after an hour, try a different one. Tell your doctor or nurse if these medications do not relieve nausea and vomiting. They can make suggestions or prescribe other medicines.

If you have nausea and vomiting at certain times of the day, take or ask for your anti-nausea medicine at least 30 minutes before that time. For example, if you often have nausea or v with meals, take an anti-nausea medication at least 30 minutes before your meal. If you vomit within 1 hour of taking your anti-nausea pill, you can take another pill.

Anti-nausea medications can cause side effects, including sleepiness, constipation, or diarrhea. Most people feel that these side effects are worth the benefit of having their nausea relieved.

Fatigue is the most common symptom felt by people with cancer. Many factors, in addition to the underlying cancer itself, can contribute to cancer related fatigue. These include anemia, poor nutrition, depression, medication side effects, poor sleep and being less active.

What you can do to help:

- Tell your healthcare team. It’s possible that you may need medicine, a nutritional supplement or a blood transfusion to help with your symptoms.

- Think about the “4 P’s of Energy Conservation”

- Prioritize: When you have more than one thing to do, begin with the most important task to make sure it gets done.

- Plan: Plan your activities in advance to avoid doing extra trips.

- Pace: Never rush. Rest often and rest before you feel tired.

- Position: Sit when you can to do tasks. Avoid bending and reaching too much.

- Rest when you need to. Take short naps of 10 or 15 minutes rather than longer naps during the day. Too much rest, as well as too little, can make you feel more tired. Save your longest sleep for the night.

- Balance your rest and activity. Keep track of when you feel most tired and when you have more energy so you can plan activities at the best time.

- Try to limit the length of visits with family and friends. In hospital, ask your nurse if you need help limiting the length of time visitors stay.

- Update family and friends with group texts/emails or social media (or delegate this task!).

- Let others help. Ask a friend or family member to update others on your condition and to help grocery shop, cook, or babysit.

• Light exercise such as walking around the block or unit can boost your energy.

Many of our chemotherapy drugs can cause temporary hair loss by interfering with the normal growth of hair follicles. Hair loss can happen anywhere on your body. It may start with gradual thinning of your hair, or hair may come out in clumps. Hair growth resumes when you are done taking chemotherapy.

What you can do to help:

- Be gentle with your hair. Use a mild shampoo and a soft hairbrush.

- Consider cutting your hair short before it falls out. A family member or salon can help you cut or shave your hair, or a nurse can assist you on the inpatient unit.

- Use hats, head scarves, or wigs to keep your head warm and protected.

- Protect your scalp from the sun using a hat or scarf and/or sunscreen.

- If you’re interested in a wig, save some locks of your hair, so you are able to match colour and texture.

- Prepare your family and friends. People close to you, especially young children, may need to be reassured when they see that you are losing your hair.

Chemotherapy and some other drugs can cause memory changes (sometimes called “chemo brain” or “chemo fog”). You may notice you’re forgetting things more often, having trouble focusing, or having trouble doing more than one thing at once (multi-tasking). Your memory and concentration will get better after treatment is over, but you may notice problems for a few months or longer after treatment.

What you can do to help:

- Use timers. Use cooking timers and safety features like automatic shut off. For example, oven timers, stove timers, and small kitchen timers. Consider wearing a watch with an alarm or using the alarm feature on your cell phone.

- Use calendars. Keep one with you to record dates and contacts. Many cellphones have a calendar function as well.

- Track meals, sleep and activities to help you figure out if there are patterns that affect your attention and memory.

- Write things down. Write out questions for your healthcare team and record answers right away. Write things down when the information is detailed or complicated. Try making “To Do” lists and check off items as you complete them.

It can be common to develop a dry or sore mouth several days after chemotherapy. This is referred to as mucositis (“mew-co-SYE-tiss”). You may notice small canker sores on the inside of your cheeks or lips, under your tongue or on the base of your gums.

What can help:

- Tell your nurse or doctor if you have pain or notice sores in your mouth or throat. Special mouth rinses can numb your mouth and throat to make it easier to swallow. Pain medications can also be used for comfort and to help you eat.

- Brush your teeth with a soft toothbrush. You will be prescribed a special mouth rinse to use before breakfast and at bedtime. Add water it if tastes too strong.

- Use lip balm to keep lips moist and prevent cracking.

- It is safe to floss if this is your usual routine but stop if you notice bleeding gums.

- Try soft foods that are moist, bland and easy to chew or swallow such as eggs, smoothies, cream soups, yogurts, cooked cereal, mashed potatoes, ice cream and ground meats. Gravies, sauces and soups can help soften foods.

- Eat whatever you can manage but try to avoid hot, spicy, acidic, hard or crunchy foods such as toast and hard tacos.

- Ice chips, hard candies and popsicles can help relieve dry and sore mouth.

- Remove dentures often to give your gums a rest. Keep dentures clean.

Some of the chemotherapy drugs can damage the long nerves in our body. Symptoms of can be numbness or a tingling (pins and needles) or a burning feeling in your hands or feet. Other symptoms can include constipation, or weak muscles in the hands and feet. Usually, these side effects are temporary. But for some people, they may last for several months or even be permanent. Let your healthcare team know if you have any symptoms of weak muscles, numbness, tingling, or constipation

What can do to help:

- Talk to your health care team if you have any of these symptoms, there may be helpful treatments your team can prescribe.

- Be careful with sharp objects so you don’t cut yourself.

- Move slowly and use handrails when you go up and down stairs.

- Use no-slip mats in the bath and shower; install grab bars.

- Protect your feet with shoes, socks or slippers.

Having pain does not necessarily mean that your cancer is progressing or getting worse. A number of our procedures, and therapies can cause pain as a side effect. There are different types of pain, which can be managed with different types of medicines. Your nurses and doctors can help with pain relief and we even have pain specialists and our palliative care team that can help relieve very severe pain.

What you can do to help:

- Tell your health care team if you are experiencing pain. They can suggest comfort measures and sometimes pain medications that can help your body relax and rest.

- Discussing what triggers your pain, the description of the pain, its patterns and severity can help your health care team treat it. For example:

- Where do you feel pain? When did it start? What makes it better or worse?

- What does the pain feel like? Is it dull, sharp, burning, pinching, stabbing?

- How strong is the pain from 0 to 10, (0 is no pain, 10 is worse pain imaginable)

- Try to stop pain before it gets worse: Sometimes people wait until their pain is bad or unbearable before taking medicine. Pain is easier to control when it’s mild. If you wait, your pain can get worse, it may take longer for the pain to get better or go away, or you may need larger doses to bring the pain under control.

- Tell your healthcare team if you have any side effects from your pain medicine. Many people choose not to take or stop taking their medication because of side effects, but they can often be managed.

- Try relaxation techniques. Relaxation can help relieve tension and pain.

- If possible, continue to stay active. Gentle stretching and movement may help.

Side effects of treatment (such as hair loss, hormone changes, fatigue and emotional changes) can affect your sexuality and the way you see yourself. Common sexual changes include body image concerns, low sexual desire, vaginal dryness, difficulties with erections, pain during sexual activity, and relationship changes.

What can do to help:

- Talk openly about your feelings with your partner. No one can read your mind, not even someone you have lived with for years.

- Being physically active improves self-image and energy.

- There are many ways to express your affection and be intimate with your partner. Touching, holding, cuddling, taking walks, good conversation, hugging, kissing, and dancing are important aspects of intimacy.

- Talk with your health care team if you have questions or concerns about sexual or body changes, birth control, periods (menstruation) or fertility.

It is safe to have intercourse once your blood cell counts have recovered. Platelets should be higher than 50 and white blood cells should be 1.0 or higher. It’s important to use some sort of birth control to prevent pregnancy while you are receiving cancer treatment. If a pregnancy happens with an egg or sperm that has been damaged by chemotherapy or radiation, there is an increased risk for birth defects.

Suggestions to make sex more comfortable:

- Use a water or silicone-based lubrication to help with comfort and dryness. It should be BPA and Phthalate free, the pharmacist at your local pharmacy can help you find a suitable option. If it smells, tastes or tingles, it shouldn’t be used.

- Find positions that are comfortable. Use pillows as extra support.

- Use medical grade silicone or glass vibrators or personal assistive devices. Wash them before and after in hot soapy water. Do not use antibacterial wipes on them.

Some chemotherapy drugs and radiation can cause skin rashes, redness or darkened colour, itching, dryness, peeling or acne-like blemishes. These skin conditions usually go away once treatment is over. Your healthcare team can suggest a treatment specific to your symptoms.

What you can do to help:

- Tell your health care team about any skin changes right away.

- Wash with a gentle soap to reduce your risk of skin irritation and infections. Wear loose, comfortable clothes.

- In the shower, use warm water instead of hot. Gently pat your skin dry rather than rubbing it.

- Use a gentle moisturizer to soften your skin and help it heal if it becomes dry or cracked.

- Keep your nails short and clean. Use cuticle cream instead of cutting the cuticles.

- If you cut or scrape your skin, clean the area at once with warm water and soap.

- Petechiae (“puh-tee-KEE-ah”) are small purple or red spots on your skin that happen with a lower platelet count. They are not harmful but need to be watched.

- Your skin will become more sensitive so you should protect your skin from the sun by wearing a wide-brimmed hat and clothing that covers your arms and legs. Apply sunscreen with a SPF of at least 30 when you go outside, even if it is cloudy.

- Avoid hot water bottles and heating pads, they can seriously burn your skin.

Having trouble sleeping (insomnia) is a common problem during treatment. You may have insomnia if you are unable to fall asleep, wake up often during the night or wake up very early and can’t go back to sleep.

Pain, anxiety, depression and some medicines can affect your sleep. Insomnia makes it harder to cope with other side effects of treatment. It can affect your mood and energy level, cause fatigue and make it hard to think and concentrate.

What you can do to help:

- Take only short naps (15-20 minutes) during the day.

- Be as active as you can during the day. This can give you more energy for the day and help you sleep better at night.

- Go to bed and get up at the same time every day.

- Your doctor can give you a sleeping pill to help you sleep, especially on the inpatient unit. Think of this a short-term solution. Do not depend on it to sleep.

- Relax before bedtime – have a warm shower, read, listen to music, audiobooks or podcasts. Avoid looking at the TV, cell phone screens and other electronic devices.

- Do not have caffeine at least 6 hours before bedtime. Caffeine is found in coffee, non-herbal tea, chocolate, and soft drinks. Try not to eat a heavy meal or drink within 2 hours of bedtime.

- Make sure your bed, pillows and sheets are comfortable. Block out distracting light, or use a sleep mask. Ear plugs are available on the inpatient unit.

- Get up and go into another room if you’re tossing and turning in bed. Stay there until you feel sleepy enough to return to bed.

- On the inpatient unit, your occupational therapist (OT) can help with sleeping issues and other strategies to make you more comfortable.

Complications from Transplants

A stem cell transplant comes with its own risk of complications, including:

What is it? An infection is the invasion of harmful bacteria, viruses, and fungi or parasites in your body. These germs can come from an external source (outside the body) or from germs that you may already be carrying in your body.

How common is it? They are very common and can vary from mild to life0treatening.

What is the timeline? You are at the greatest risk in the first few months after transplant, especially while your white blood cells are low. Infections can also happen in the months and even years it takes for your new immune system to mature.

What causes it? Your immune system is weak in the weeks and months after transplant. It could be compared to the immune system of a newborn baby and needs time (12-18 months) to mature and fully protect your body from invading organisms.

What can I do? Take all your prescribed medications (antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals) as instructed, follow our infection control guidelines and let us know immediately if you have any signs of infection (ie: fever, chills, cough).

What is it? GVHD happens when your new donor cells (the “graft”) attack your body’s cells (the “host”). There are 2 different types of graft versus host disease:

- Acute GVHD – Can affect your gut, liver and/or skin

- Chronic GVHD – Can affect any part of your body

How common is it? GVHD is very common. It can vary from mild to life-threatening. Chronic GVHD can impact your quality of life and increase your risk of infections.

What causes it? GVHD occurs when your new donor cells think your own body’s cells are foreign, or don’t belong, and attack them.

Why is GVHD Helpful? GVHD can be beneficial in mild to moderate cases. This is because of something called the “graft-versus-leukemia” (GVL) or “graft-versus-tumour” affect. GVL occurs when new donor cells attack any remaining diseased or cancerous cells in your body. Although this graft-versus-leukemia effect is a form of GVHD, it is helpful because it lowers the chance for your disease to return or “relapse” after the transplant.

What is the timeline? Acute GVHD usually starts in the first few weeks of transplant once your new cells have engrafted, and last up until day 100. Chronic GVHD is typically GVHD occurring any time after the first 100 days of transplant.

What will my health care team do? We give you “anti-rejection” medications before and after your transplant to prevent GVHD. There are medication options to also treat GVHD if it does occur.

What can you do? Take all your prescribed medications as directed, attend all your follow-up appointments, and let your health care team know of any symptoms you notice after your transplant. Protect your skin from the sun and avoid smoking.

Signs of Acute Graft Versus Host Disease:

- Stomach or Gut: mild to severe diarrhea, stomach cramping, nausea & vomiting

- Skin: a rash that looks like a sunburn on your hands, feet and face. The rash may spread to other parts of your body and may be accompanied by a fever.

- Liver: tenderness in upper right stomach, itchy skin, jaundice (skin and/or whites of your eyes turn yellow)

Graft failure is a rare but life-threatening complication of transplant. This happens when your new donor stem cells do not successfully grow in your body. This usually happens within the first weeks after transplant but can happen anytime. Your doctor will talk to you about options if this happens. In some cases, there is the possibility of having a second stem cell transplant.

A stem cell transplant affects your whole body and can cause mild to severe damage to your organs. These symptoms can appear in the months and sometimes years after transplant and are caused by the chemotherapy, radiation and other necessary medications you received. Infection can also cause damage to your organs.

Heart: Severe heart problems are rare but mild heart problems can be common (i.e. blood pressure changes). Tell your health care team immediately if you have any heart symptoms (chest pain, fast heartbeat, etc)

Bladder: Mild kidney and bladder problems can be common, severe kidney problems are rare. Continue to drink fluids and stay hydrated after transplant and tell your health care team if you notice pain with urination or blood in your urine.

Lung: Lung complications can be caused by treatment but are usually related to an infection. Mild breathing problems can be common, such as temporarily needing a small amount of extra oxygen. Severe breathing problems are rare, such as needing a machine to breathe for you. Look after your lungs with deep breathing exercises, staying active through treatment and avoiding smoking, dust and mold.

Bones: Bone density loss can be a common complication and increases your chances of eventually developing osteoporosis and/or breaking a bone. There are medications to prevent and treat this but good nutrition, regular weight bearing exercise (walking, jogging) and strength training are things you can do to prevent bone density loss.

Hormones: Reduced hormones levels, including the thyroid, pancreas and sex glands, can be a mild but common complication. You may need to take medications to balance these hormone changes.

Transplant Recovery and Long-Term Follow Up

The medical term for when your blood cells recover is called ‘engraftment’. Engraftment is when your donor’s stem cells begin to make new blood cells. Engraftment usually starts 10-14 days after your stem cell transplant day but can take longer. As your blood counts recover, you will notice the side effects and symptoms from the chemotherapy (and radiation) improve.

Once you’ve been cleared for discharge from the hospital, you’ll continue to be seen as an outpatient in the Leukemia/BMT Daycare Unit up until “Day 100” (100 days after transplant) or longer. Your appointments will be every 1-3 days at first, then gradually less frequent.

Sometimes it may be necessary for you to be readmitted to hospital after being discharged. This is usually related to complications like GVHD and infection. This can feel like a big setback but don’t feel discouraged, it can be relatively common.

As you approach “Day 100” you will repeat many of the tests you had before your transplant, then meet with your attending physician to discuss the results and plan for the future.

Note: Some patients may need to continue to receive treatment in the Daycare unit beyond Day 100.

After Day 100, you’ll be referred to our Long-Term Follow-Up (LFTU) Program. Through the program you will receive individualized support to address your symptoms and long-term side effects after transplant.

Generally, it can take roughly 12-24 months for you to return to a relatively normal lifestyle after transplant. Adjusting to life after your stem cell transplant can feel like a slow recovery. You will likely still have good days and bad days. It will take time for you to step back into your roles, such as being a parent, spouse, employee and friend again. Be patient with yourself as you adjust and recover.

Stem cell transplantation can have long-lasting or late-onset effects on your body and as such you need to be monitored and examined regularly for signs of complications. The L/BMT Program of BC offers long-term follow up care through our comprehensive program.

The LTFU Program can offer you support, treatment and education post-transplant. The LTFU team consists of a multidisciplinary team of healthcare providers who specialize in oncology care. The clinic focuses on identifying, preventing, and managing any long-term and late effects associated with transplant. Your visits will involve assessment and management of complications or issues you may be experiencing, and development of a plan to support your future health.

If you have any questions that cannot be answered by your personal doctor or if you and your doctor have determined that consultation from the LTFU Program is needed, we are here to help. Patients who have lost contact with the Leukemia/BMT Program of BC after their transplant are also encouraged to get in touch with us. To reach us Monday through Friday during the hours of 0800 until 1600 call (604) 875-4111 ext. 64335 or email LTFU@bccancer.bc.ca. For emergencies, please call 911 or go to your nearest emergency department.